The Right-Hand Shore – a novel in family stories

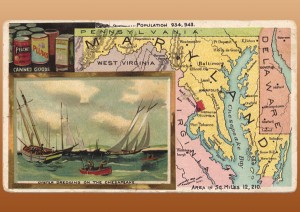

I grew up in the Boston area, the son of a publishing executive, but from my first years my family spent the summers on our ancestral farm on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. This is a low, flat landscape where the land ends and the water begins almost seamlessly; all the vistas are longitudinal, broad fields, the sweep of rivers and inlets, near distant points of land where loblolly pines still cling to life on uncertain footings, and in the far distance, the Chesapeake Bay (above, the view across Chester River to Hail Point, 1910). The first Tilghman, a Catholic refugee from England, waded ashore in 1657, and Tilghmans have remained there ever since, fortunes rising and falling, clinging to their own part of the New World.

Tilghman House, 2012

By the late 1940’s when we started going there, the farm — the main house, the dairy, the barns and outbuildings, the grounds — had fallen into decay. Indeed, it had fallen back into the nineteenth century, with farming done as much with mules as tractors, milking by hand with the iconic milk buckets set out in the sun for pickup, no electricity. When we summered in the main house, which was called the Big House, we scavenged a crude but comfortable existence out of the forgotten detritus of a once very fashionable estate. If we had any question about what had gone on there in the past, all we had to do was walk into the family graveyard, ten feet from the house. What information those gravestones did not provide was lushly and constantly filled in by the stories and the legends that seemed as much a part of this farm as the buzz of the locusts in the trees, the sting of jellyfish in the river, and the sweet tang of cow manure whenever the wind came out of the east.

Tilghman family graveyard, 2012

In my new novel, The Right-Hand Shore, my character Edward Mason spends an entire day listening to tales and ends up feeling “mauled by the past.” For my brothers, and me this immersion in stories was a more gradual process, but all-pervasive. Some of these stories, about suicides and watchful ghosts and betrayed ambitions, were within the purview of the Big House and my privileged forebears. And some were tales of loved ones sold South during slaveholding times, of the rising tide of Reconstruction and the abyss of Jim Crow, all told in whispers by the black families that mostly in bondage and servitude, had shared every piece of the history, side by side, day in and day out, with the Tilghmans for 300 years.

Miss Sue Williams, model for Mary Bayly, on porch with guest, 1910

The Right-Hand Shore opens with its own conclusion: a meeting on a porch in a vast estate on the shore of the Chesapeake Bay in1920. What is happening involves the same set of circumstances of my earlier novel Mason’s Retreat: the dying maiden owner of the estate, Miss Mary Bayly, is interviewing distant cousin Edward Mason in an attempt to determine whether she will bequeath the farm to him as a direct descendant of the original Mason immigrant. Mason’s Retreat moves forward in time from this meeting; The Right-Hand Shore goes back in time to discover how this situation has come to pass.

Of all the family tales I have drawn from in both these novels, this is the one that is most factually accurate. It was in this manner that my grandfather, a bit of a rogue and an infinitely self-centered man, secured the ownership of the farm in 1918 from his cousin, Miss Susan Williams. “Miss Sue” was a fabulously wealthy Baltimorean recalled to this day as reformer and philanthropist on both shores of the Chesapeake, but remembered less warmly by descendants of her servants and laborers as a harsh mistress. This sentiment was summed up in an insult scratched in a pane of glass: “Susan Williams 2-faced.” Miss Sue hung over my childhood experiences on the farm just as the trials and mysteries of Miss Mary hangs over The Right-Hand Shore: how did it come to this, a wealthy society lady from Baltimore running a dairy farm across the Bay?

Front of Tilghman house, 1910

In The Right-Hand Shore we learn that Mary had a brother, Thomas, who, as the son, was the designated heir to the estate. In the novel, had he still been on the scene, there would have been no reason for Edward Mason to assume ownership, and Edward and his family would have been spared some of the sorrows that occur in Mason’s Retreat. But the brother is no longer available, and in the novel, we discover why.

So it was in my family history that Miss Sue’s brother set in train some of the events in my life. The facts are in a clipping from the local newspaper: in September of 1895 a young man named Otho Williams, heir to the Tilghman estate, shot himself to death in a second-floor room overlooking the family burying ground. He was unmarried and left no issue.

Tilghman House from family graveyard, 2012

The newspaper article suggests that this tragic event may have been a terrible accident whilst cleaning a firearm, but no one in my family and in the communities around us would have any of that: Otho Williams shot himself because he had fallen in love with a black servant and he was not allowed, by family or law, to marry her. As a child in the 1940s and 1950’s, the suggestion of a family suicide – complete with a bloodstain still visible on the floor under the straw matting – was rather titillating, but the theory that he had done it because of a forbidden love for a Negro woman just did not seem that remarkable. Falling in love seemed to me the sort of thing that might have happened on this place in the past, where blacks and whites, workers and owners, had lived and died in such intimate daily intercourse. What joined us was simply a matter of place, and the stories grew out of this land.

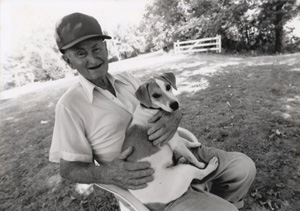

Lee Faulkner with dog, 2005 |

Lee Faulkner cultivating with mules, ca. 1940 |

A second story came indirectly to me from the black community not many years ago, through a white man named Lee Faulkner who came to work on our farm in the 1940s and died only recently. Over the years, during the writing of Mason’s Retreat and researching of my new novel, I had realized that Lee’s knowledge, his memory based on the stories he had heard (he could only barely read), reached deep back into the nineteenth century community of former slaves. So one day, having just learned from reading the will of the Tilghman who died in 1853, that there were some 60 slaves in his inventory of property – a slaveholding of immense size at that time on the Eastern Shore – I asked Lee if he knew what happened to them. His answer became the scene that opens The Right-Hand Shore, the incident in 1857 where a cruel man I call “The Duke,” Mary and Thomas’ grandfather, herds almost his entire population of slaves into a field along the Chester River and sells them to a slave trader from Virginia. “That’s what happened to the slaves,” said Lee Faulkner. How did he know? He had worked with the grandchildren of Tilghman slaves.

Farm hand, model for Abel Terrell, 1910 |

Restored Tilghman slave house, 2012 |

Another story that found a place in my book was inspired by a 1894 newspaper clipping in which it was reported that a young black man’s body was discovered in a barn on my family’s property. He had been murdered. The story dropped the curious comment that the victim was known to be literate, clearly an educated young man. As far as I can tell, this murder was never solved—perhaps the authorities hadn’t tried all that hard. In the first chapter in The Right-Hand Shore, when Mr. French tells Edward Mason that “this is where they found the boy’s body,” I am picturing the barn, still standing, in which this young man was found, and I am already on my way to solving his mystery in the speculative universe of my fiction.

Canned peach label, ca. 1910

One final discovery provided the narrative thread to bind all these stories together. I read in a local history book that between 1865 to the mid 1890’s, Queen Anne’s County had been “one big peach orchard.” During peach season, the Chester River was alive with steamers picking up peaches for delivery to Baltimore or to the trains of the Eastern Shore for shipping to northern markets or to canneries. And then, as I have tried to tell it in The Right-Hand Shore, the whole enterprise collapsed, a twenty-five year boom, the dot com bubble, at least in local terms, of nineteenth-century Maryland.

Restored mule barn, 2012 |

Maryland trading card |

Having now acknowledged so much factual, or at least, legendary basis for much of the events in The Right-Hand Shore, the unrepentant fiction writer must hasten to say that the entire work is a work of make believe, that where no facts exist I made them up; where historical evidence might have contradicted my tale, I ignored it. So as I reflect back to growing up surrounded by tales, I can only acknowledge, at the end, that little of what I heard or, even more unreliably, what I remember, may be true. Likewise, for Edward Mason listening to a day of stories in the French’s’ house in The Right-Hand Shore, what the French’s tell him can hardly be free of embellishment. Curiously, that doesn’t seem to matter to me or, I think, to him.

Farm manager’s house, model for the Mr. French’s house, 1910